'When The Night Comes' Review: A Fun, Supernatural Murder Mystery

Note: When the Night Comes contains mature situations – while it’s no more explicit than a Mass Effect game, it’s probably equivalent to an ESRB M or a PEGI 16/18.

It’s uncommon that my partner and I both fall in love with the same game. I usually prefer platformers and turn-based strategy while he can sink hours into a 4X (games like Civilization, Stellaris, Europa Universalis). However, both of us loved When the Night Comes, the supernatural visual novel by Lunaris Games. The visual novel offers a compelling story, solid art and music, and some of the most queer-friendly romance options I’ve ever seen in a game. And it’s only $5.

In the game, you play as a Hunter, someone tasked with suppressing malicious supernatural creatures, in the small town of Lunaris. The town has been plagued by a series of gruesome murders, and you’re dispatched to investigate. Along the way you’ll meet colleagues in the region’s anti-supernatural-problems organization, some townsfolk, and friendly supernatural creatures.

When the Night Comes (which I’ll be abbreviating as WTNC) is a linear visual novel – while you’ll have dialog options, the overarching supernatural murder storyline doesn’t change extensively based on your choices. The core murder plot is fine, and the setting is quite good – I actually wish we spent more time learning about the lore world, about how the enforcers and hunters organization came into existence, how magic in the world works (can anyone learn magic, or just a few people), but what was there was handled well, and the developers have ample space for a follow up game or story in the same setting.

But the biggest reason the story worked so well for me was the characters. By the time I was done with the first chapter or two, I wanted to help the people in this world. They were sympathetic, they had their own stories, they had interpersonal relationships that existed with other characters – while many of the characters are potential romance options for the player, they felt like actual characters in the story, not just targets for the player to romance.

On that topic, the game offers six of romance options, plus two polyamorous relationships options within the six, plus the option to not romance anyone. You can romance Omen (the demon), Alkar (the lycan), Piper (the hunter), August (the enforcer), Ezra (the witch), or Finn (the vampire). The game page on itch has a nice infographic with everyone, including their genders and pronouns.

Depending on who you chose to pursue (or not pursue), you’ll have content specific to that route that functions as a side story within the larger plot. Completing one playthrough took about six hours for me.

As I mentioned, romances in WTNC are optional, so you can play through the mystery of the town without romancing anyone. Additionally, none of the romances are gender locked, so you can romance anyone regardless of your player’s gender. This style of game romance is often referred to as “player-sexual,” as the sexuality of a character is fluid and will accommodate the player character.

Player-sexual characters can trigger debate, so I want to touch on this here. There’s discussion that the practice can erase bisexual and pansexual individuals, because if the character’s sexuality is only defined in relation to the player, then that’s no longer a possible identity for the character. Also, if done poorly, player-sexual characters can, perhaps paradoxically, effectively quarantine queerness in a world by erasing it unless the player opts-in. Todd Harper’s amazing article for Vice on Fire Emblem: Three Houses explained it well:

Fire Emblem’s relegation of queerness to “a choice you can make, I guess” while at the same time emphasizing the opposite-gender pairing off of characters is a perfect example of heteronormativity in action. If queerness exists in those worlds, it’s something you add as the player, not something the game’s world provides for you to have a meaningful experience with.

There’s also a common argument you’ll see online that, in real life, most people aren’t gay and you may get rejected by people because you’re the wrong gender, so romances in games should reflect that – but, given this argument can be simplified down to ‘being queer in real life sucks, so it should suck in games too,’ it’s often employed in bad faith.

All that said, as a gay guy who is used to games telling me I don’t get a romance option (or I do, but only with this one side character who has a fraction of the dialog of everyone else’s options), I’m personally fine with player-sexual characters if they’re handled well, and WTNC does handle them well. Some characters in WTNC do discuss past relationships, and will sometimes pair off with other non-player characters of the same gender if not romanced, so they do have a sexual identity that is not purely linked to the player, and queerness exists within the world without the player dragging it in themselves.

For games like this, where I suspect the majority of players will want to pursue one of the romance options, giving the player more options can help them feel more included in the story. WTNC offers male, female, and non-binary romance options for your character to pursue, and both poly and non-poly options – the game feels incredibly welcoming and accessible as a result.

And, to WTNC’s credit, all the characters were compelling. While I suspect the developers might have had their own favorites (*cough* Finn *cough*), all the characters, and all the romance options, were solid. After years of putting up with “you’re gay, so only this side character is available for you,” the fact I had issues choosing whose story to pursue because they were all available, and I was interested in all their stories, felt amazing.

For the record – I ended up pursuing the romance with Omen and Alkar, while my partner went with Finn and Ezra. While I understand my partner’s choices, Alker has a moment mid-game which made me think, “I will stand in front of a horde to defend you from [redacted] ever happening again,” so… yeah, ended up with the lycan and the demon. But the fact that I felt sympathy for the characters, and felt invested in their injury, shows how strong the writing was.

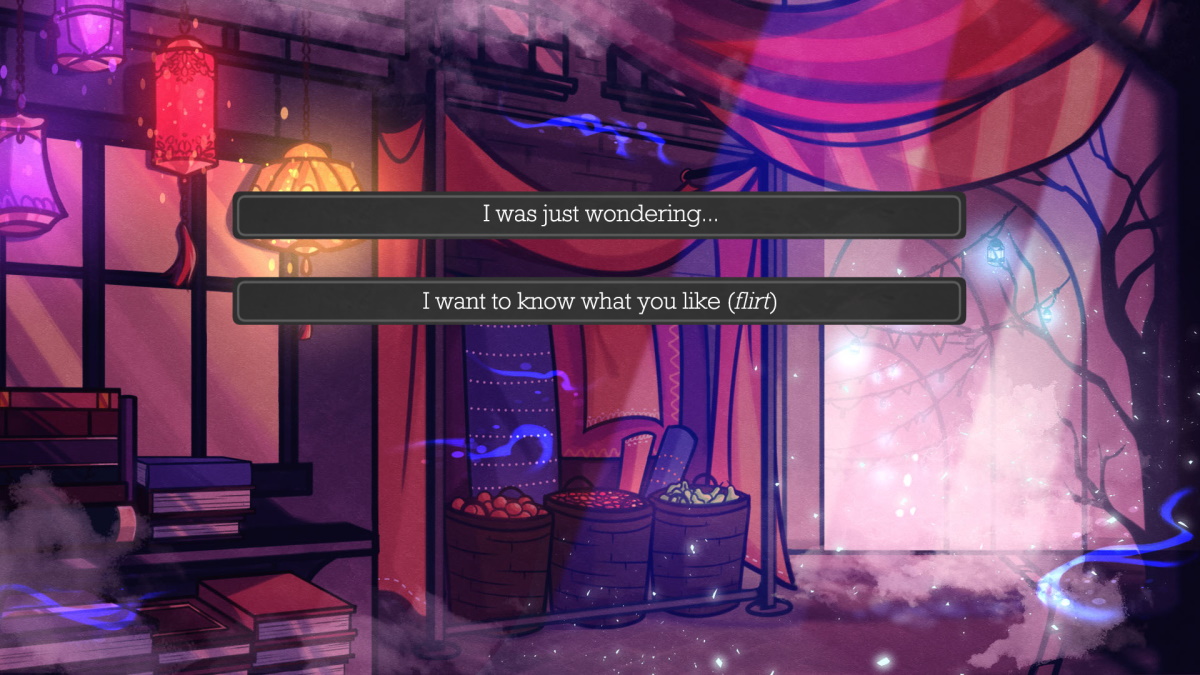

WTNC is incredibly upfront about what dialog options mean – options that cause your character to flirt with another character are marked as flirting, and I found I enjoyed this. When I attended a panel on narrative design in games at PAX, there was a line that stuck with me: when presenting different options for the player, the impact of the player’s choices can surprise them, but the action taken by their character should not – the player’s decision should be respected.

To explain why this is important, we should talk about the game that’s infamous for violating this rule: L.A. Noire. L.A. Noire gave the player control over a detective, and the player would be offered options about whether to believe the suspect or witness they were questioning, or perhaps press them a bit more about their answers. And players were surprised when “doubt” could mean anything from “are you sure” to aggressive accusations of murder.

We can contrast this with a game like Monster Prom, which also has a large degree of player choice. In Monster Prom, if player is offered to “toss a tennis ball and hope the werewolf pack chases it and goes away,” and the player chooses that action, then that is exactly what the character will do. Now, is the result going to be that the werewolf pack goes away? Maybe. But your character will throw the tennis ball.

You can see the difference – in L.A. Noire the action taken by the player’s character is unpredictable, whereas in Monster Prom the effect is unpredictable. The former is bad because the player ends up feeling like they don’t have control over their in-game character, while the latter provides that level of control while still enabling the player to be surprised.

For a game like WTNC, where you’re playing yourself (vs controlling an established character on their own story), that control is extremely important, because it allows you to feel connected to the story and your in-game avatar, and it’s why I liked that the game lets you know if you’re about to flirt with someone. I was playing a gay character, and I wanted to pursue a romance with a guy in-game. Having the game offer clear indications of how your character would behave with the different dialog choices ensures I didn’t end up on a romance route I didn’t want to be on.

Though, on the topic of routes, the game is quite generous with saves (there are 54 save slots, not counting automatic and quick saves), and the game is very clear when you’re locking into a specific romance route, so you’re able to save, and later go back and explore other routes. Additionally, you’re always able to scroll up to rewind and jump back to previous choices.

While I love the game, I did encounter a few minor issues related to branching rejoin points; when the player is presented with a choice, and the choice is played out, eventually that choice needs to rejoin the main narrative – sometimes things that happened during the ‘choice’ scene aren’t accounted for in the rejoined narrative.

For example, there was a scene in which your character has the option to lie to another, possibly evil, character. If you choose this option, your character makes a gesture to one of your friends, and they indicate they understand you’re lying. However, once that scene plays out, your friend expresses confusion at your actions (how dare you say to this person you were going to work with them), despite they acknowledged you were lying earlier – it’s as though the main dialog had them being surprised at your actions, and the game didn’t process that you just went through the “lie, but make sure friend knows” option.

There are a couple of these hiccups throughout the game, but they’re all small (and likely less noticeable if you’re not playing with ‘reviewer brain’). And, I’m somewhat sympathetic to this, considering editing and testing branching narratives is miserably difficult for small teams. More choices are great, but each branch multiples the number of test cases.

I could also quibble ever so slightly on the game’s in media res style of throwing terms and lore at you and explaining it later, but that’s because I personally like knowing about the fantasy lore of world I’m interacting with, so not having the term ‘enforcer’ clearly defined irked me. That one is personal preference, not a defect.

All my complaints really are small compared to the overall product. The game is exceptionally well made, has hours of content, the characters are interesting, the romances are solid and inclusive, and the core murder plot drew me in. It’s place on itch.io’s ‘Top Rated’ list is well deserved, and it’s one of the best visual novels I’ve played in recent memory. Buy it.