Supergiant's Greg Kasavin Discusses Language and Early Access

Back in 2019, I had the pleasure of interviewing Supergiant Games’ Creative Director Greg Kasavin. We spoke about how the acclaimed studio got started, how they developed a custom language for their game Pyre, and how early access has shaped their most recent game, Hades.

Sean Z

How did Supergiant Games get started?

Greg Kasavin

Supergiant started with my colleagues Amir Rao and Gavin Simon. The

three of us were working at Electronic Arts in Los Angeles and on the

Command & Conquer series, and we were making real time strategy games.

But in 2009, we were really inspired by the kind of burgeoning

independent game development scene. What was happening there with these

games like Braid and Castle Crashers and Plants vs. Zombies and

World of Goo… They were totally different games, each made by really

small teams and made with a great deal of heart and a great deal of

quality and felt very fresh. And we were playing these games while

working on a much bigger team going, “Wow, it’s amazing what can be done

by a small group of people.” And that’s when we started thinking about,

“Maybe we could give this a shot ourselves.”

Amir and Gavin left their jobs, dropped everything, and moved into Amir’s dad’s house and started working on Bastion, our first game. And then we formed our team of seven over the course of that game’s development. And the seven of us have been there ever since for 10 years, through our subsequent games Transistor and Pyre, and now Hades.

We’ve grown a little bit; we grew to 12 people for Transistor and stayed that size through Pyre, and now we’re up to 17 people, but that’s still, I think, relatively small. And staying small is really important to how we operate. But we’re so lucky to have some fresh blood on the team to offset us grizzled, old-timers who’ve been at it for a while. I think we just really value creative chemistry that we have on the team.

We try to create an environment where we do the best work that we’re the most excited about, and to jam our games full of that work, and see what comes out the other side, and hope our players enjoy it, and thankfully they have thus far and that’s why we’re still here.

We self-funded Bastion back in the day, and the success of each of our games has paved the way for the next. We are at a size where we can only kind of work on one major game project at a time, so it’s made the 10 years go by almost in a flash it seems, reflecting back on it now.

Sean Z

One thing we spoke about several years ago was the development of

language in your games, and, in particular, the language in your game

Pyre. I was surprised to learn that Pyre has its own functional

spoken language in the game. Could you discuss that?

Greg Kasavin

For Pyre, we created an imagined language called Sahrian because the

characters from the game come from a country called the Commonwealth of

Sahr. And the origin of it is a couple of things. Pyre is a pretty

like narrative rich game, but we knew that there was no way we were

going to be able to fully voice all the story content in the game

because it has all of this procedurally generated story content, where

the characters in events, like aspects of them such as their race or

their backstory, all of that is pulled together in the way that the

narrative is presented. We did the math and there are 200 million

different permutations of the epilogue of the game alone. So, we were

not about to voice record all of that, as you can imagine.

So with voice recording everything off the table, it was still really important that we give this cast of characters in Pyre a voice and a personality because we were trying to make this big character driven game where you get to know these characters and get to grow attached to them, and having a voice there is so important. We developed this language so that you can have these little snippets of stuff that sounds like words to give them that sense, to make them come alive in that way, especially since the game has different characters of all shapes and sizes and some fantastical races and stuff like that. Just hearing really different types of voices could enhance these different characters.

So that was one reason we wanted to do it. The other reason is that we actually did a little bit of it on our first game, Bastion. Late in that game you encounter a faction of characters called the Ura. We start you off fighting these things that you don’t really care anything about, arguably semi-mindless seeming kind of basic monsters or something, but by the end of the game, you’re fighting people, and they had to seem like they were people who have that sense of agency and so on.

It was a well-regarded aspect of Bastion. So with Pyre we decided to go all in on it, and that meant coming up with internally consistent rules around pronunciation and starting to like come up with specific terms that could be used throughout the game, as little touchstones to make you feel like it was a real language instead of just straight up gibberish. There are games that use gibberish really well, The Sims is the classic example, but it’s not meant to sound like real words in that game. Whereas with Pyre, we wanted it to sound like actual words that people were saying.

I have a broad fascination with languages. My first language is Russian, though English is the language I know by far the best. I think growing up I was exposed to different languages, so I just kind of love the sound of them. I was pulling together different ingredients from different languages. And the main one on Sahrian, the language of Pyre, was Latin because we wanted this kind of ancient feeling world. And I think so much of it is kind of encoded in our minds, but when you hear Latin, it just feels old. Just automatically, it just seems ancient and medieval or whatever. So if it sounds kind of like Latin, it’ll just make you feel like you’re in an ancient world just automatically. That was kind of the starting point for the vibe of it.

To add more dimension to it, we have different characters from different parts of this country. Essentially, we had to come up with sub-dialects of this language, for the equivalent of a Boston accent or an Alabama accent or a California accent or whatever.

With this character, who is much more educated, and this other character, who’s much more lowbrow, how do they sound different? And some of that is in the performance, but some of it is also in the writing. We have these subtle little differences in some of the words.

Sean Z

Could you give us an example of that?

Greg Kasavin

Oh man, off the top of my head? Your character in the world of Pyre is

called The Reader. Reading in the world of Pyre is forbidden it’s a

world of characters who are largely illiterate, but your character has

this forbidden knowledge of how to read, and it’s an ability that holds

great power. So, we establish this term in Sahrian, the term for reader

is “Ligaratus.” So, many characters just call your character

“ligaratus,” and you hear the term ligaratus used by those characters,

you’re like, “Oh, hey, that must mean reader,” as you hear it a few

times.

But then you meet a character called Pamitha who is this harpy-type of character. She’s part of a wicked race called the Harps, and she has a more informal way of talking to you. In the writing she refers to you as the “Reader Darling.” She almost has kind of a femme fatale quality. So she’ll say, “Reader Darling, how you doing?” And you hear her say Ligaramis instead of Ligaratus. And it’s just a small twist on it. You hear it. It’s mostly similar. You see “Reader Darling” written, you hear Ligaramis said, and it’s like, we absolutely don’t expect players to notice that, but we hope that they feel it.

This wasn’t an aspect of the game that we expected to stand out necessarily. It’s just there to add to the flavor of it and make it feel more lifelike, but it was really cool to see some players pay attention and notice, and feel that we did put some, I guess, some effort into it as it were. Because we had to write, even though it’s technically, to even if you could call it gibberish, there’s always a subtext.

I had to write it in English and then translate it into Sahrian and make both versions available to the actor, because the actor reading each of these lines, they need the subtext of the line. Because while they don’t know these words, they need to know that this line means “I’ll get you back you SOB” and read it that way. So I would write it in English that way and say, “Here’s the translation, and here it is phonetically, here’s the rules of pronunciation. So now do this.” We would record hundreds of these lines for each actor and then they would fumble the pronunciations, so we had to discard quite a bit and only use the ones that sounded good to us to fit the specific moment in the story. It ends up feeling, hopefully, cohesive in the context of the game, even though we left so much on the cutting room floor.

Sean Z

How does having the different language reduce the number of combinations

you needed to record? You have your original English text, and the

translated Sahrian, but you still have all the procedurally generated

combinations. How does that help?

Greg Kasavin

That’s a good question. Even though I wrote all these lines with

specific subtext, in many cases, I did not care about what the intent of

the line was when hooking them up in the game. I would just listen for

the one that felt right for what was written, because we wrote and

recorded the Sahrian, in many cases, months before the actual game

writing was complete. It was never meant to be one-to-one because again,

it would be hundreds of millions of lines. If it was one-to-one with

everything, we weren’t going to do that. It had to be a little bit more

reusable than that. And then even with many lines, we’d say like, “Give

us a … " If a line has the subtext of like, “what the hell?”, give me

a, (questioning) “what the hell?” as well as an (angry, frustrated)

“what the hell?” And then I can maybe use both of those inflections in

different situations.

I had a library of tonal material for each speaking character in the game, and I would go through all their story content scene by scene, and hook up an appropriate line. There are many scenes in the game. For example, so there are many scenes in the game where nine different characters can be in the scene depending on the circumstances of the game. And in those scenes, I had to do this work times nine essentially for all the different playable characters.

Sean Z

So, even with the procedural generated story, you still had to assign

this positive-sounding intonation with this positive line, all by hand?

Greg Kasavin

This process was fully manual. You chose this path, so this character

is with you in game; that’s the procedural part, how it chooses the

character. But then, for each permutation I had to manually construct

the mapping, since I have to manually write their dialogue anyway, how

does this character react in this situation and so on? That sort of

thing.

I think I said it on a panel earlier today - someone asked how do we feel about Pyre in hindsight? For me, I think Pyre contains a lot of the best work I personally I’ve ever done. It felt like this was my shot.

Each of the games I’ve worked on here has been my shot at one thing or another, but Pyre was my first opportunity to create a game with a big cast of characters with intricate relationships, where I was really concerned with making sure each of these characters had a really distinct personalities, distinct motivations. As part of that, they had to have a distinct voice. That’s why this Sahrian thing it both benefited the specific characters and then it benefited the world building to make the world feel like it was real.

I should mention we use English extensively in the game as well. Whenever you get into one of these rites, these ancient rituals where your freedom is at stake, there’s this announcer voice presiding over the rite who speaks in English to you, in an almost snotty, often humorous kind of insulting way.

We wanted to play with the role of language in the game. You, as the reader, can read English. It’s nothing to you, but playing as your character, reading this stuff is second nature to you, but something that you uniquely can do. So, while you can understand this English-speaking character in the same way, Sahrian, the foreign language to the player, that’s the normal language to everybody. That’s the language everybody understands. English is the language that you uniquely understand. English represents a forbidden language that’s like Latin to us.

And the game has since been translated into other languages. I refer to English because we’re speaking in English. It’s also in German and French and stuff like that.

Sean Z

Did localization have any kind of impact on how you handle language?

Greg Kasavin

Localization was extraordinarily challenging on Pyre because of the

procedural generated nature of the story. The construction of sentences

is based on assumptions of English grammar and sentence structure.

Sean Z

Can you give an example of that?

Greg Kasavin

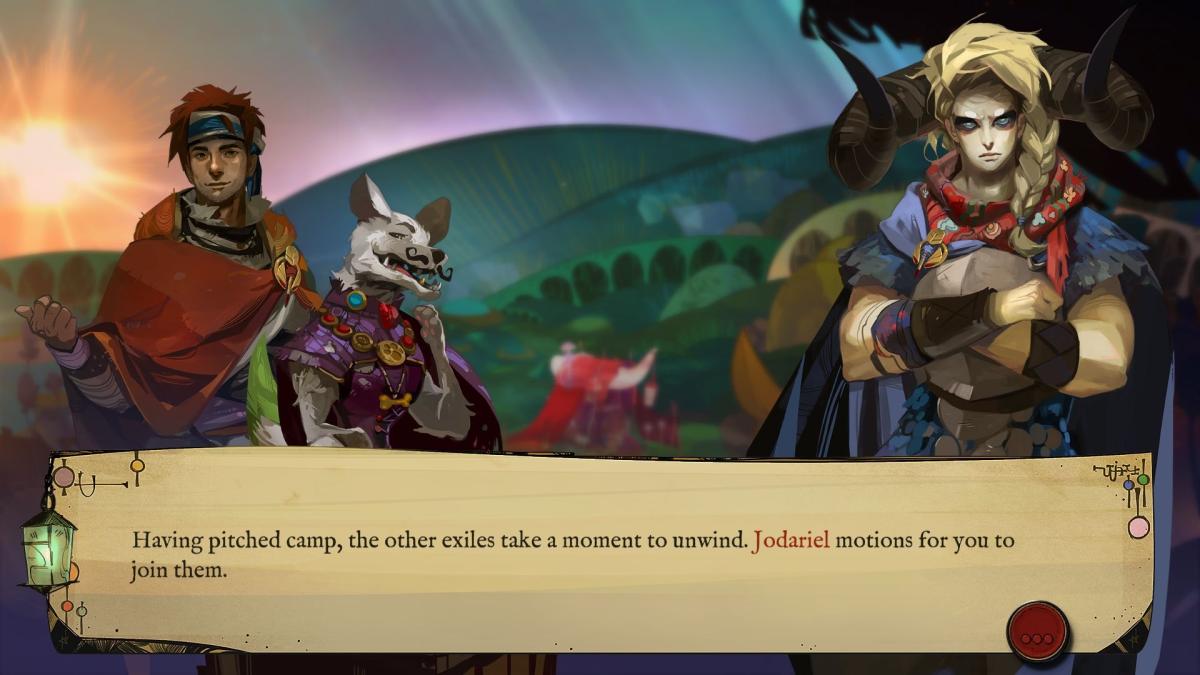

One of the first characters you meet is named Hedwyn. Let’s say the

game has a sentence, “Hedwyn says he wants to go West,” but Hedwyn may

not be in your party. Maybe Hedwyn has already ascended and returned to

the Commonwealth. So, in this situation, the game will choose Jodariel,

who’s a demon. And it will be, “Jodariel says she wants to go West.”

Male, female pronouns, the subject-verb structure of English is unique

to English. Different languages have different rules around pronouns,

different rules around sentence structure. And German does not work the

way English works, and French does not work the way English works and so

on, so we have to fundamentally reconstruct the dialogue. The languages

don’t all follow the same rules so we have to rewrite the rules of the

sentence construction for each language, and that made it really

difficult.

Sean Z

Did you localize Pyre yourselves or did you outsource the work to

another team?

Greg Kasavin

We worked with an outside team to localize the content, but we had to

work with them to do the part where it becomes coherent. Like. the game

does not have just a script, it just has these sentences that are filled

with bits of data that are almost like a Mad Libs. If you think of a Mad

Libs, it’s just like a bunch of blanks, so they have to translate these

things that only end up making sense once you put them through the game

and the blanks are filled in, so that made it very challenging.

Sean Z

As a writer, how did that compare to something like Bastion or

Transistor which was a much more linear, straightforward narrative?

Greg Kasavin

Bastion and Transistor definitely had branching as well. In

Bastion, the narrator will say in the very first level, as you’re

running away from something collapsing, the narrator says, “Kid just

keeps running.” But if you’re tumbling around, he’ll say, “Somersaulting

like crazy.” And he only says, “Somersaulting like crazy,” if you’re

actually somersaulting. In Pyre, it was just like exponentially more

material. It made things exponentially more complicated, but it was an

exciting challenge.

Sean Z

You’ve discussed how you’ve worked to develop these complex,

procedurally-generated branching stories within your game Pyre. What

did your team decide to do for Hades?

Greg Kasavin

One of the things we enjoyed working on as part of Pyre was writing

a story with a big cast of characters with intricate relationships and

so on. With Hades, we have another great big cast of characters.

To back up briefly, the thing about Bastion and Transistor, although they have a strong story to them, they have very small casts of characters. They can feel very lonely by design.

Although there’s like warmth there, and you feel this great bond with the characters who do exist, they’re these like sprawling worlds with very few inhabitants. With Pyre we wanted to make an inhabited world where you could make friends and go on this big road trip with them. With Hades, we were like, “we love the great big cast of colorful characters thing, let’s do that again, but this time they’ll be fully voiced.”

I think, as much as I loved working on Sahrian, if there is something more direct, it makes the character feel even more real if you just hear them talk in the language you do understand. And it’s more important to the specific flavor of Hades, and the directness of Hades to have them do that.

There’s still a ton of variability in Hades, but it’s around the game state. It’s that we have all these characters talk to you about all sorts of really specific different things, depending on the exact moment that you’re in.

In Hades, you’re the prince of the underworld of Greek myth, who’s trying to escape. Your father, the lord of the dead says, “You ain’t never getting out of here you ignoble brat. How dare you try to defy me? Be my guest if you think you could get out of here, go get out.” You’re like, “Oh yeah, I’ll show you.” So you’re trying to get out. Along the way, you have the help of the Olympians who appear—“Oh, we have this long-lost nephew. Come join us, we’ll help you get out of this bad family situation that you’re in.”

These different Olympians will say, if you’re low on health, “Oh my God, you’re in … What’s wrong man? What’s gotten into you?” Or if you’re in a particular area, they’ll say, “Oh man, you’ve made it all the way to the Asphodel Meadows, that’s great. You’re making good progress.” They respond very specifically to the game context. It’s procedural and [the lines] can mean different things, but it is the opposite of scripted. I come up with as many different possible contexts in which a character can talk to you and then we load them all up into the game and have the game hold the right one for the right situation.

It’s designed fundamentally to be deeply nonlinear and replayable, so that this content can happen in any order. And the great thing about it is that, even as the person writing it, I should have zero surprise around it. Right? I know exactly what all of it is. Yet, it surprises, just like Pyre did, it surprises me all the time because of the specific ways it can sequence together. There’s Aphrodite walking over there. Things like, you meet Aphrodite after you’ve met Athena in a run, because even that part is randomized, and Aphrodite would be like, “Oh, Athena has already gotten to you?”

The gods will respond to other gods who you’ve encountered, and that comes from the randomness of the game structure itself, and then the narrative falls into place to make it seem grounded in the world. While we’re making a rougelike hack and slash game, a style of game that many other developers have pursued, in the same way we felt like we could make something unique in the action RPG space with Bastion back in the day, we felt like we could add a distinctive narrative component and a sense of cohesion to this type of a genre.

Sean Z

How does having early access affect the narrative development? Because

you now have live feedback coming in?

At the same time, how does early access affect the players? Do players play the game once in early access, and then put the game down because they believe they’ve completed it, even though it’s still in progress?

Greg Kasavin

At the inception of the project, it was a really fun thought exercise.

I think if you’re a fan of Supergiant games, the idea of us making an

early access rougelike sounds almost antithetical to everything we’ve

ever done because we’re known for these games with a traditional

beginning, middle and end. We’ve prided ourselves on our games having

like a sense of completeness to them. So, an early access game, what’s

going on there? But we were like, “How do we do this?” We’re excited to

try it, but we wanted it to have all the stuff that we like putting into

our games. When it comes to the narrative, our approach is essentially

to think of it almost like this initial early access launch would be

like a pilot episode.

We introduce the story, we introduce the cast of characters, and then with each major update that we roll out every month or two, we add to the story, we introduce characters, we introduce new situations, we build on existing characters and so on. The players experiencing the game in early access get to see the story unfold. And we’ve said that we intend to reserve the final narrative outcome for when early access is complete. Right now, the game does have an ending of sorts. It has a huge variety of different endings, given the replayable structure, but it’s not the complete narrative.

Even though that the game is early access, we have inworld explanations for the lack of completeness of certain aspects of the game. It’s always fun to think about how to justify aspects of the design in the context of our worlds, and I think we do it in a playful way that’s consistent with the tone of the game.

The feedback we’ve been getting has been really encouraging. To answer the other part of your question, I’ll answer it by way of comparison, and we can come back to Pyre. With Pyre, from a writing standpoint, I worked on that game for three years. And you play test it along the way, even with say dozens of people or hundreds of people, but even still, you don’t really know what you have until you put it out there. You work on it for three years, you put it out there, it’s this big cathartic moment as a developer, “What does everyone think?” People then burn through the game.

Pyre is a much longer game than Transistor, but even still, people burn through it in 48 hours or whatever, and then that’s it. All through development, you’re asking yourselves as a development team, “Oh, does this character work for people? Is this part okay? Should we be doing more here, more there?” With early access, with Hades, we introduce a new character, we find out right away if people like this character or what people like about this character, and that part has been really great from a writing standpoint actually because it lets me sharpen my own instincts around what aspects of the story are working really effectively, what are the characters who are really resonating with players.

We wouldn’t put in a character if we didn’t want them to resonate on some level, but of course some characters are by design meant to be more central than others. Are the central characters hitting the right notes for people? It’s helpful being able to move forward with the confidence of having had that feedback from a lot of players along the way.

To get a little bit more specific with Hades, the game has a sense of humor to it despite the kind of dark veneer, the underworld setting. It’s a game called Hades, you don’t assume a game like that would be funny necessarily. We try to play into those expectations and subvert them in a way by having some humor to it. But humor in games is tough. Not everyone has the same sense of humor.

With our early access launch, we have some humor in there, but it’s like, “Man, what are people going to think of this?” And it turned out the feedback we were getting around the humor was really positive. People liked the humorous aspects of the game, so it made us be able to move forward kind of with more confidence that this is something, this really is the tone of the game.

With that feedback, I think we have a really firm grasp of the tone and where the game should be silly and where it should be serious. We want a tone that is aligned with the play experience itself, and I think roguelikes, if you’ve played roguelikes, they have a very slapstick quality where one moment you’re on top of the world, you feel like you’re totally unstoppable. You’ve got the perfect build, you’re destroying everything in your path, but then one boneheaded mistake and you … It’s like stepping on a rake and having it smack you in the forehead. You feel like such a bozo you made a stupid mistake, and you could either be really mad at yourself, or you could kind of laugh at yourself, be like, “Oh my God, I can’t believe it.”

And we want the game’s tone to have that kind of quality of laughing with you, not at you. A character who’s self-effacing in the face of failure, but is very determined. So, when he fails, he’s like, “Oh my God. I can’t believe I did that,” but he’s going to go and try again, he’s not going to get super pissed off at himself. And hopefully, that aligns with the player’s own experience, helps players push through their inevitable setbacks and be willing to try again as part of the core experience of the game.

Sean Z

Roguelikes can be notorious for their difficulty. Is Hades leaning

into that? Is it very difficult to complete the game?

Greg Kasavin

It’s a really good question. We set out to make Hades … We say

that it’s a game where you don’t have to be a god to experience what is

exciting and enjoyable, although if you happen to be a God, it’s got you

covered. It can have a very significant and tightly crafted challenge to

it. But, while we love the experience of rougelike games, but for sure

they sometimes … Like, what’s so exciting and thrilling about them can

sometimes be like hidden behind a really steep difficulty curve. You

have to climb this mountain to be able to have this experience.

We do want the barrier to entry on this game to be lower. We have a narrative to it. There are other reasons to enjoy Hades besides just the thrill of barely scraping by. That thrill is there too. And, being a game where you play as an immortal character, when you suffer these setbacks and get sent all the way back to the house of Hades (the starting point), you have the ability to get stronger in a permanent way. So not only are you as a player picking up, both as a player and as a character, that you’re picking up knowledge of what’s ahead.

Because for example, while there are random aspects, it’s the same guardian boss initially that’s going to be facing you at the end of Tartarus. You come back to her and you know who she’s going to be, and they have a conversation about it. It’s a rematch now, and you’ve learned a little bit more and you’re maybe a little bit stronger now too.

So we want for players both through their experience and through these other systems in the game to be able to overcome some of the earlier setbacks that they may have run into, and for it to ultimately be a game where, if you’re reasonably invested in this game, you care about it, and you want to get to the end, you’ll be able to reach a satisfying sense of narrative closure like you have been able to in our past games. However, it’s a game designed around replayability and it will keep going. There will be more story, there’ll be more to discover from there that, if you get better and better at the game, if you’re super skilled and stuff like that, there’s going to be plenty more stuff that you could see.

Sean Z

You mention more there’s stuff to see. If we come back to early

access, is there content, like endings, that won’t be revealed until the

game is out of early access?

Greg Kasavin

There will be new stuff. Like I said, the ending of the game and other

aspects of the narrative we deliberately are going to hold back. It’s

not like we’re sitting on it and we haven’t put it in. We’re just going

to make the endings after everything else, knowing what we want to do

with it. But that will be in our version 1.0 — the last big update for

our full launch. For right now there’s a mix, tons of unique one-off

content, these bigger story moments that never repeat, and a lot of

content that is designed to be repeatable. But before any of it repeats,

you would have to have looped through the game like 20 or 30 times, so

hours and hours of play before a small line will repeat, for example.

So, by the time the line repeats you probably won’t remember it anyway, because it’s not a line that should feel kind of repetitive if you were to hear it again. That’s how we designed the narrative of the game. It should feel like a unique forward-moving story no matter how many times you played the game over and over, because you’re an immortal god with no sense of the passage of time. You could just infinitely play the game as a denizen of the underworld and just keep having these unique experiences as you run into these different kinds of characters, stuff like that.

Sean Z

As the game develops, how far away do you think you are from 1.0

launch?

Greg Kasavin

We expect to exit early access sometime in the second half of this year. Even

though we have most of the full game structure right now, we still have quite a

ways to go because we want to give ourselves lots and lots of time to iterate on

it and improve every aspect of the game, and just to, hopefully, fulfill all the

potential that early adopters have already said they see in it. We love working

on this game and with each of our games, we want them to live up to our past

work if nothing else and have the potential to be the favorite game that we’ve

ever made for our fans out there. That takes us a certain amount of time and we

just want to take all the time that this game needs to make sure we’ve done

everything that we really want to do with it.

And then from that point forward, that version 1.0 launch is not necessarily the end, it’s kind of like at that point we’ll see how it goes, we’ll see what everybody says when we design the world of Hades. We designed it for early access from the ground up, and unlike games like Transistor that may have no obvious room for a continuation once it gets to the end, a game like Hades can be more of a world where there are many stories that we could tell here.

Sean Z

And that was by design? It was meant to be sequel-able?

Greg Kasavin

Not even sequel-able, more like a living game where we can continue to

add content. We don’t intend to have all 12 of the Olympians in the

game. Canonically there’s like the 12 Olympians. A certain number of

them will be there as part of the story, but that’s not to say the other

ones couldn’t join the fray later.

That’s not meant to be a commitment of any sort, it’s just the sort of thing we care about. There’s so many gods, monsters and heroes of Greek myth that we could imagine in this universe. If you think about Greek heroes, they all die, so they all wind up here [in the underworld] too. We have these characters like Achilles and Theseus that are in the story already, but there are many more that we could imagine being there potentially.

The story won’t feel incomplete without them, but the point is that we could have more stories. That’s the potential that we see in the game in the long term. But, that’s getting a bit ahead of myself—we have to see what the response to the game is at launch. So far it’s been great getting positive feedback and everything, but we have plenty more to do. Our full focus is nailing each of our major updates in the process of getting to that version 1.0, and then from there, it’s a game that hopefully we can justify continuing to work on.

Sean Z

As we come up on time, just to close us out, you’ve now written all

these various games. You’ve created lots of characters. Were there are

any characters that were your favorite to write?

Greg Kasavin

Oh man.

Sean Z

It’s always fun to ask this question.

Greg Kasavin

No, it is. I love the question, but as a father of two children, you

are straight up asking me to choose a favorite. It sounds disingenuous

or something, but these characters are, they’re my baby. I love our

characters very deeply. I remember all of them vividly from Bastion to

Transistor to Pyre, now to Hades. We had to nurture them into

existence. And then once the games launch, they’re kind of like, now

that they’re their own thing, whether people like them or don’t like

them, they’re kind of like, I no longer control them, they’re out in the

wild now. But I love them dearly. But oh man.

Having said that, there’s some characters in Pyre that were very near and dear to my heart. There’s the character Sandra who’s the only optional character in Pyre. She’s the character in the Beyonder Crystal who you can really get to know over the course of the game. But, while your relationship with her can go very deep, it’s purely optional. It was fun to think about a character who had been trapped in a crystal ball for 837 years and what that would do to a person. I was really glad to see Sandra stand out to many Pyre players. She was a character, that during the course of development, there were times when we didn’t know if Sandra was going to make it because she was often looked at as, “Well, we need the necessary characters. Do we really need this Sandra character?” I’m like, “We need the Sandra character, please let me try it.” I love her a lot.

There’s a character called Volfred Sandlewood in Pyre also who is central to the story. I love trying to write complex characters, and to me he’s a complicated guy. You start off feeling one way about him and I think end up feeling a different way about him, and I really enjoyed trying to thread the needle on that. He had to come off as very persuasive because he’s a leader. But he’s a leader who, when you first meet him, you’re not sure if maybe he’s up to something. You’re suspicious of him and you don’t get off on the right foot, but you come around hopefully to respecting him and understanding that he wasn’t trying to pull one over on you, he was sincere.

It was trying to make a character who you, as a player, could be genuinely persuaded, and it was a really interesting writing challenge. But man, I could go down the list.

I love our antagonist characters. Especially our antagonist characters; Zulf in Bastion, Royce Bracket in Transistor, Oralech in Pyre, Lord Hades himself in Hades. I say antagonist, because to me it’s more interesting than a villain. It’s a distinction. An antagonist is someone who opposes you, not necessarily someone who is just trying to create evil. They’re just someone who wants something that is opposite from what you want. Are they a terrible person? Maybe, but not necessarily. Our lives are filled with antagonistic forces and people who don’t want what we want, but they’re not necessarily bad people. Sometimes it’s just the circumstances that put us at odds. And our games deep down, despite they’re wildly different settings and themes, they’re about character’s trying to understand each other in the world around them. And I think our stories always have empathy at the heart of them, understanding one another, even when someone may have done something really terrible, at least understanding what led them to do that.

So I enjoy writing antagonists and going through the thought process of where did this person go wrong? Where did this go astray? What caused this person to hate someone or something like that? What led to that to really get in their heads that way? It’s really fun and invigorating from a writing standpoint to try to understand the character that way, and I think my love for them comes from that.

I feel like I honestly know the characters in my stories just better than I know most people. In spite of all my blabber-mouthing to you right now, I am a very … I live almost like a hermetic lifestyle. I don’t have much of a social life. I am very introverted in social situations, so I know these characters better than I know most humans. And I connect with the world through writing, and then I connect with other people through their own response to our games. That part is very gratifying, when people enjoy our worlds and characters and stories, I feel like I connect with them that way more than is often possible just having a normal conversation with them.

That’s part of what I love about the process and the result.

Note: This interview was originally published as two separate articles on GeekDad back in 2019. They’ve been merged and lightly edited here.